Nightingale Magazine

The Lines the Guide Me

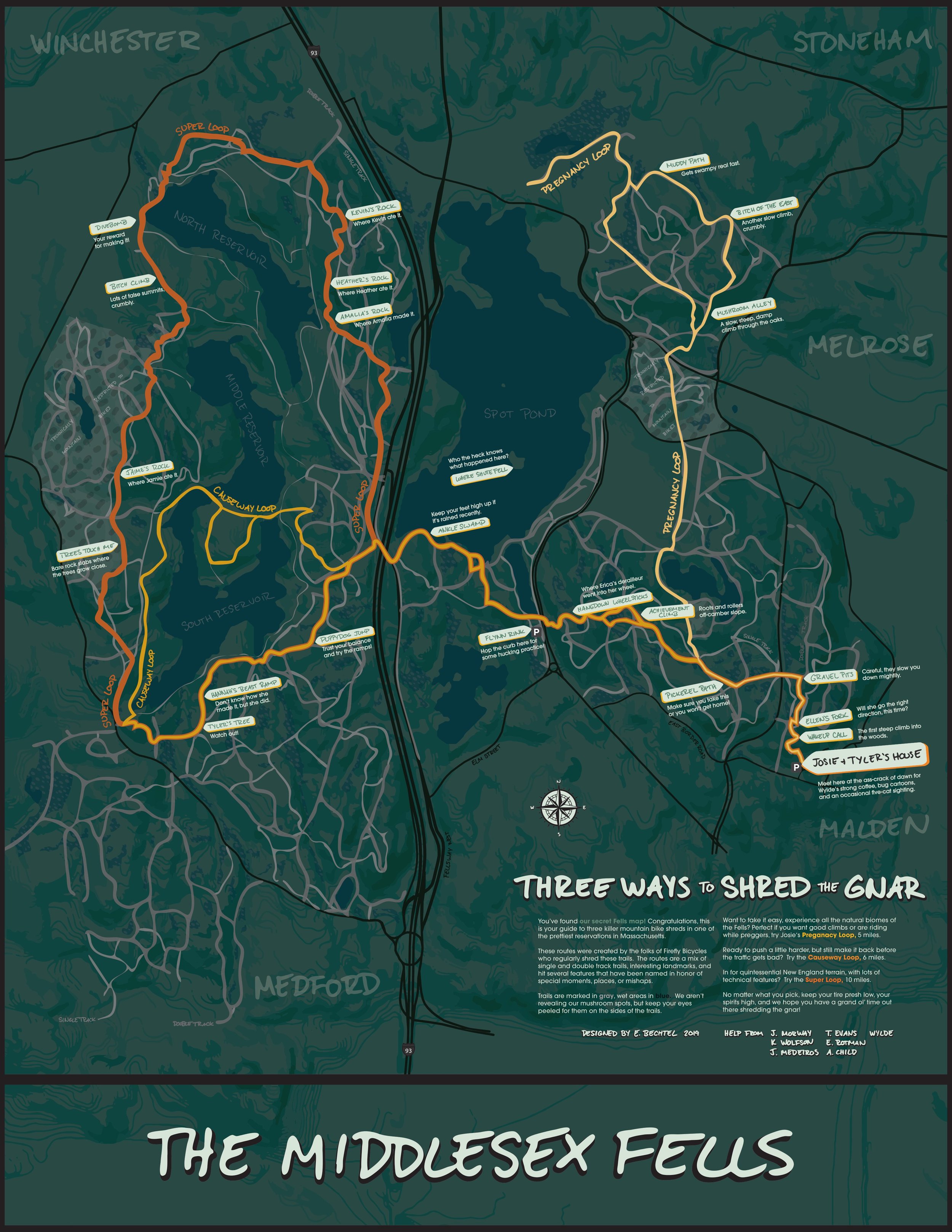

The following article was published in the Data Visualization Society’s magazine Nightingale in May 2023. It’s about this map I made for a friend.

One of my earliest projects where I truly felt part of the data viz world was about making a trail map.

My intent with this map was that I’d give it as a gift to two special friends, but in the years since, I’ve discovered that it’s actually a gift from Past Ellen to Future Ellen. This trail map guides me back to where it all started for me (I literally got the idea for it while riding my bike). It reminds me that a career path can start with anything, even a super personal project for no one other than yourself and your buddies. And it reminds me that anything that is meaningful and important, even to just one person, can be put on a map.

This trail map was not designed for a wide audience. The lines are not for any average person who needs directions, but only for a few people for whom the trails hold special meaning. Its markers aren’t for a general public seeking interesting sites, but rather for those who created memories at those spots. Its labels aren’t useful to anyone but us because they are mostly nods to inside jokes.

Still, the map—and the significance it has in my private and professional life—does hold a lesson for those who may be skeptical that a highly personal project with a limited “target audience” can still be a meaningful undertaking.

It Started With a Friendship

Six years ago, I was working at a bike manufacturing shop in Boston, Mass., called Firefly, which produced custom titanium bicycles. The shop was started by three friends—Tyler, Jamie, and Kevin. Firefly produced some of the most gorgeous bikes in the industry. I joined their shop as their finisher, which means that I transformed freshly welded titanium into the polished, anodized, intricately detailed bikes that sparkled from their Instagram and Flickr posts.

I adored every day working there. I got to work with my hands, got so covered in grime that I went through exfoliants faster than shampoo, and got discounted bike parts that my wife, Erica, and I needed for our own bike projects. (She and I had met through a women’s bike mechanics group, after all, so we did a lot of bike stuff together.)

But most of all, the reason I loved being there was because I got to spend time with people who loved their work—not for the money, but for what it allowed them to do. Indeed, the three entrepreneurs lived and breathed biking, and they especially loved to “shred the gnar,” which is adventure lingo for doing something hard that feels exhilarating.

When I started working at Firefly, even though I adored working on and riding bikes, mountain biking eluded me. It looked risky, and bro-y. One spring day a few months after starting at Firefly, I casually mentioned that I would love to join them on one of their mountain bike rides if they were ever doing a beginner route.

Tyler graciously heard the subtext of what I was really asking: Can you help me learn how to shred? He suggested that Erica and I come by early some morning before work and go for a ride with him, his wife, Josie, and their two-year-old daughter sitting in the kid seat. Afterall, his backyard opened up to the Middlesex Fells, a forest preserve with lots of well-maintained trails outside of Boston.

Our first ride together was utter magic. After some 6am coffee and a quick practice riding over some obstacles in their driveway, we hit the trails. The family guided us around the routes, pointed out good spots to look for mushrooms along the way, and took it slow over the trickier parts of the trail. The crisp air and golden light of sunrise gave everything a sepia-toned and endorphin-rushed feeling of glee. That morning ride turned into a promise to do it again the following week, then into regular Thursday mornings, and then into an entire summer’s worth of shredding the gnar.

Some days we’d fall hard and scrape our palms, or get flat tires, or send a drop—meaning, make it over without dying—that we’d been working on for weeks. That summer gave us pounds and pounds of forageable mushrooms that we’d spot from the trail and fry up for dinner. It gave us a way to watch our bodies and skills change. And it gave us time to build a deep friendship.

Making the Map

Through that magical summer, I harbored a deep down secret: I knew I wasn’t going to work at the shop for much longer. As much as I loved the job, I knew that a bike finisher’s salary was not going to support the family that Erica and I wanted to build together. So I started doing data visualization projects on my own to teach myself the craft, and eventually asked Tyler, Jamie, and Kevin to reduce my shop hours so I could enroll in Northeastern’s masters program for Information Design. They graciously said yes, even though we all knew that it meant the inevitable end of my bike career. I was wracked with equal mixes of guilt for knowing I was going to leave, and gratitude for their generosity in letting me do something that would eventually take me away.

One of my courses that first fall semester required me to make a visualization about a path or route that was meaningful to me. My mind went straight to the Fells and the summer we had just spent shredding the gnar. I decided to make an illustrated map to memorialize our excursions. As a school project, it would be a perfect exercise in cartography and illustration, but if it turned out nicely I thought I could also frame it as a thank-you gift when I eventually left the shop.

So I spent weeks meticulously gathering map layers:

For the basemap, I wanted to include elements of more formal trail maps, like contour elevation lines, hillshade, pattern markings to indicate land or forest type, and nearby roads and trails—even though I didn’t need the to-the-meter precision that most people rely on for navigation. These layers came from a lot of different sources: some were from government maps that were in PDF form and miraculously still had the layers labeled when I opened them in Adobe Illustrator. I snagged the roads using Mapbox Studio. And the rest of the Fells trails were from a shapefile from a state government geographic website that I exported as SVG paths, and then manipulated them to get an “illustrated” look.

As we continued shredding into the fall, I secretly recorded the GPS routes of each shred and imported those lines into Illustrator. Whenever we’d pass one of “our spots” on a shred, I’d pause and drop a pin on Google Maps. Back at home, I’d meticulously go through the pins and turn them into map markers with little stories.

Designing and writing for each marker on the map transported me back to all the times I’d passed that particular spot. As I designed markers for those places— like “Mushroom Alley” or “Bitch Climb” or “Trees Touch Me”—I’d remember how the trees looked, what line I’d have to follow to avoid particular rocks or roots, and all of our treasured experiences there.

Writing about it now—a graduation, two jobs, a pandemic, a wedding, and a baby later—I’m surprised and delighted by how easy it is for this map to guide me back to that place and time after so much life has happened since then.

What It All Means Now

My inner critic says: why make a trail map that is meaningful to so few people? It may seem so insignificant, given that so many other people have traversed these trails. Not only on mountain bikes, but on foot, with assistance, with shoes, without. People, animals, generations of plants and fungi and bacteria. These trails also exist in geologic time—before these trails, these areas were wooded with no paths. And before that, there was a mile high glacier on top of everything, depositing the moraines on which the trails now sit. And before that, the Appalachian orogeny was pushing mountains up higher than the Rockies, and before that, there was nothing but high-energy atoms congealing in space.

What is my trail map, in the context of all that? My little illustrated trail map, noting a few places where a few random humans fell, or didn’t, and maybe laughed together, is peanuts amidst all of that. But I think sometimes, it’s important that we humans make maps that have no purpose other than to connect us to each other. Data viz, design, and mapping can be used to:

Mark the spot where your life changed forever—a fateful connection? A goodbye?

Show the physical path as a metaphor for an emotional path—maybe that journey helped you reach an epiphany.

Give some permanence, weight, or significance to something that happened to you by literally putting it on the map.

Record and share the story of why someone is special to you.

At least, that’s what this trail map did for me.

I have a baby now, a 9-to-5 job, and I live 45 minutes away from most of the Firefly crew. I can’t predict when I’ll be able to shred again, or when I’ll get back to the Fells, or when I’ll be able to regularly watch the intimate details of seasonal change pass over a New England forest the way I did that summer.

But making that trail map helped guide me towards the career I now deeply love. It helped me tell some friends how meaningful they are to me at a time of goodbye. And now, it guides me back to that sepia-toned summer of Shredding the Gnar anytime I want.

Other Works